Seattle has its megachurches and Portland has its cool. So are Cascadian megachurches cool?

After fifteen years of living in Vancouver, but also visiting Seattle and Portland pretty regularly as well as various points in between, I’m not so sure.

I have witnessed the rise—and, usually, fall—of a startling number of church plants. In fact, I’m coming to think that Vancouver in particular is a kind of treacherous reef on which the ambitions of numerous church planters have been wrecked.

Yet even to some of the apparent success stories there is a shadow side. I speak of the churches in Cascadia that purport to be postmodernly sensitive and culturally clued-in—and yet really aren’t. There is less here, I think, than meets the eye.

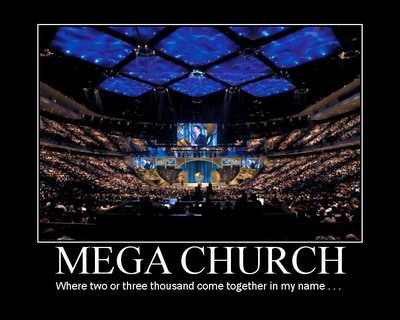

There is no doubt that such churches connect with the felt needs of many people: the numbers of attendees alone make that clear, as well as these congregations’ apparent financial means to buy or erect large meeting spaces in regions of high real estate prices.

And, despite how one might feel about the personal styles or even the doctrinal or practical shortcomings of this or that leader or church, I affirm their preaching of a recognizably orthodox gospel, a love for Scripture, a loyalty to Christ, an evangelistic zeal, an entrepreneurial flair, and a compassion for at least some of the marginalized.

What I do not affirm just now, however, is their identity as connecting with postmodern people, as speaking “the language of the culture” (as if, in these fractious times, there is a single language being spoken by a single culture), and as truly “revolutionizing church” in the light of the needs and categories of the unchurched in Cascadia.

Having great hair and serving fair trade coffee in church doesn’t make you contemporary. It just makes you “cool”—at least, as well-churched and rather square Christians might measure “cool.” Merely having a blackout stage and flashing lights and loud guitars isn’t terribly innovative: I attended, preached to, and played in churches in that mode twenty years or more ago. Indeed, that combination is now so clichéd as to evoke its own satire on YouTube, the classic “Contemporvant” video.

What if, instead, one analyzes these churches as to what gets communicated and how it is rendered in the services? What if one looks at both the content and the styles of preaching, singing, liturgy (such as it is), and prayer—as well as the leadership structures, the choices over what to fund, and even the website? One finds these congregations to be, at bottom, awfully churchy churches that haven’t innovated all that much from the nice old Baptist church up the street.

“Worship” still equals congregational singing + announcements + sermon. “Leadership” still equals men (not women) + hierarchy + authority + formality. “Communication” still equals propositional assertions + entertaining stories + appeal to the Bible + appeal to the charisma of the preacher + ethical command.

Everywhere you look, in fact, there is evidence that these churches fail to “get” the fragmentation, liquidity, and anti-authoritarian egocentricity that defines so many people in Cascadia. Yes, I suppose these congregations can be seen as refuges from the postmodern condition, and in that ironic sense they meet the needs of postmoderns. But what they mostly do, so far as I can tell, is attract a combination of (a) churchgoing Christians bored by or otherwise unimpressed with less exciting or fulfilling churches in the area; (b) “significant others” of such Christians who come to faith; and (c) certain marginalized people who enjoy the energy, kindness, and genuine Christian vitality in the church.

Let me make clear that I am very glad for these three kinds of people to find a church home in such congregations. I am pointing out only that such churches do not, because they cannot, truly connect with the typical unchurched or “dis-churched” Cascadian, who is a postmodern pastiche of identities, cultures, norms, values, modes, and practices all swirling in the gravitational field of the sovereign consumerist ego. People come to Cascadia not only to enjoy its natural beauty, mild climate, and emphasis on outdoor sports, but to flee the strictures of someplace else and do what one wants to do on one’s own terms. This is Rambo country, after all. This is where draft dodgers have melted into the mountains, where the marijuana is high-grade and low-risk, and where everyone is (escaping) from somewhere else.

What we have yet to see in Cascadia are churches that connect with the legions of artists (from rank amateurs to world-class professionals) and other “creatives” up and down the coast. If we could actually get them to come to church, how long would such people endure the design of our meeting places, finding them instantly uncongenial to an artist’s sensibilities?

What we have yet to see in Cascadia are churches that connect with people whose weekends center on hiking, skiing, sailing . . . and generally not joining a bunch of strangers in a big room where they stand to sing a long stretch of soft-pop songs and then sit to listen to someone talk about religion.

What we have yet to see in Cascadia are churches that connect with—or even have the first clue to offer—the unconventionally spiritual. We hardly even understand, let alone engage, the seekers who have seriously, not just desultorily or trendily, examined Buddhism, or astrology, or New Age thought, or Ayn Rand, or Friedrich Nietzsche, or Deepak Chopra, or our very own Eckhard Tolle.

We have yet to see in Cascadia churches whose leaders have begun to take the sociology and anthropology of their region seriously, and study as any good missionary would, the receiving culture as if he or she was leaving, say, Tacoma for Taipei or Richmond for Rangoon.

That’s why I’ve decided to get involved in this consultation. I’d like to see such churches. And if I can help to promote them, I will.