For more than two centuries the Pacific Northwest has been a difficult place for Christians effectively to share their faith. As any church planter or evangelist knows or quickly learns, understanding the history and context of this region requires the understanding of multiple cultures. In some ways Pacific Northwest culture, though often spiritual, is not “post-Christian,” since it never had much of “Christendom” in the first place!

An important place to deepen missional understanding of Cascadia is by learning from the first Protestant missionaries to the Northwest. Catholic and Protestant missionaries to the Pacific Northwest were the first relatively large groups of Americans to live among people who were non-Western (Hutchison). One of the most significant, yet understudied, of these pioneer missionaries is Narcissa Whitman.

Who Was Narcissa Whitman?

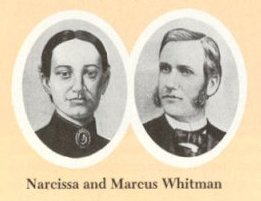

If you were required to take a high school state history class in Washington or Oregon, then you likely have heard of Narcissa Prentiss Whitman (1808-1847) and her famous physician husband, Marcus, pioneers of “Old Oregon” (Drury). In 1953 Washington State presented a statue of Marcus that stands in the U.S. Capitol Hall of Statuary. Narcissa and Eliza Spalding were the first two women to cross the United States overland, traversing what became the Oregon Trail.

If you remained awake in that state history class or actually read the textbook, you might have learned that Narcissa, her husband, and eleven others at the Whitman Mission were murdered on November 29, 1847. They were killed in a raid by Native Americans from the “Superior People” or Cayuse tribe, the same tribe the Whitmans came to Oregon to serve and save with the gospel.

You may possibly have learned that Narcissa was the only woman murdered in the raid. Yet it is very unlikely that you would have learned the reasons for the Cayuse raiding the Whitman Mission in the midst of a fatal measles epidemic, in which Cayuse children were dying and white children were mainly recovering. Nor would you probably have learned why, after months of military harassment for the white-settler-named “Whitman Massacre,” five Cayuse leaders as representatives of their people voluntarily surrendered to the new Oregon Territory government and were executed in less than a month. Tilokait, a Cayuse chief who once seemed to follow the Whitmans’ Protestantism, suddenly received Catholic baptism and was reported to have declared before his execution, “Did not your missionaries tell us that Christ died to save his people? So die we, to save our people” (Jeffrey, 220).

A major reason why you would not have learned the Native American side of the story is the development of the Whitman Myth. This brief article argues that the power of the Whitman Myth shaped the portrayal of Narcissa as a martyred heroine and suppressed her lack of fit as a missionary among Native Americans of the Pacific Northwest. This lack of fit with the multicultural environment of the Pacific Northwest is a serious problem for church planters and evangelists today. Narcissa’s portrayal as heroine is briefly described, with particular attention to popular adult and children’s biographies that conveyed the Whitman Myth through the twentieth century. Narcissa’s victimization and negative experiences with the Cayuse and Nez Perce (Cebula, 90-127) are contrasted with the Whitman Myth’s saintly martyred missionary.

Narcissa: Heroine of the Whitman Myth

The connection between America’s colonial ideal of white settlement and the Whitman Myth is dramatically shown in the conclusion to James Daugherty’s young person’s biography, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman: Pioneers of Oregon.

To the Whitmans, . . . any other course of action than the one they chose was unthinkable. They were dedicated to a Christian mission. Of what they had to give they gave all to the very end, asking for themselves nothing. There have not been many like them, but there have been enough. . . . they have not been forgotten and never will be. There have been some others of their kind before and after. The survivors of the first winter at Plymouth Plantation would have understood the Whitmans’ story. It was what they would have expected of their children (Daugherty, 157-158).

Even some professional historians, like Dorothy O. Johansen of Reed College, wrote under the influence of the Whitman Myth. She concludes her description of Narcissa with the following sentence: “The heartbreak of her two-year-old daughter’s death by drowning, the lonely forebodings of her own death, and the tragic conclusion of her life have endowed Narcissa with a saintliness her immediate contemporaries would not have recognized” (Johansen, 172). Johansen’s conclusion of the section glorifies the Whitmans as martyrs: “In late November, 1847, the last covered wagons had hardly disappeared down the river road when the Cayuses turned on the Whitmans and their crowded household in a fury of butchery and crowned Narcissa and Marcus Whitman’s labors with martyrdom” (Johansen, 172-73).

The “historical” narrative was re-shaped to portray Narcissa as a hospitable sacrificial martyr, who laid down her life for those she came to save. Jeanette Eaton’s popular biography Narcissa Whitman: Pioneer of Oregon asserts:

As for the Northwest, all its historians give these pioneers a glorious place in their annals. As interest in the early days of the [Oregon] territory grew, settlers in their letters, speeches, and memoirs told and retold the story of what the Whitmans did for Oregon. Narcissa was the heroine of all these narratives” (Eaton, 317).

Narcissa: Victim of the Whitman Myth

Marcus and Narcissa became the symbols of pioneer martyrdom. Their reconstructed story helped energize the movement of white settlers in covered wagons across the Oregon Trail. Following the “Whitman Massacre,” the U.S. Congress officially established the Oregon territory and its government in 1848. This resulted in the obscuring of Narcissa’s experience. Her voice about the story of life at the Whitman Mission, as seen in her Letters, was drowned out in the cacophony of published accounts driven by the need for martyrs to the cause of the white takeover of Native American lands.

Paul Cranston’s To Heaven on Horseback: The Romantic Story of Narcissa Whitman extends the myth to include Narcissa’s dying thoughts. As Marcus lies dying near Narcissa, Cranston, in a faux imitation of Shakespeare’s Juliet, laments: “The only relief in it is that Narcissa died within moments of her husband’s death, and so close to him, that one might say at least—death struck as she would have wished it—at the side of Marcus” (Cranston, 255). Here we see Narcissa as the victim of a romanticized Whitman myth.

The real historical tragedy was that Narcissa could not see that she was commonly viewed as “very proud” and “haughty,” toward Native Americans, even by her friends the Methodist missionaries, Rev. Henry and Elvira Perkins, with whom she stayed in 1842 when Marcus traveled back to the Eastern United States.

On October 25, 1849, almost two full years after Narcissa’s murder, Henry Perkins wrote a detailed letter describing the circumstances around Narcissa’s death to her sister Miss Jane Prentiss.

. . . I am afraid that you will never get at the real truth in the case if I do not tell you. The published accounts of that melancholy catastrophe which cut short so many lives, are all one sided. They fail almost entirely to account for the proceedings of the natives (Perkins in Drury II, 393).

Perkins sadly describes Narcissa’s lack of fit to the missionary life, which she chose and through which she suffered.

The truth is Miss Prentiss your lamented sister was far from happy in the situation she chose to occupy. . . . I should say unhesitatingly that both herself [sic] & her husband were out of their proper sphere. They were not adapted to their work. They could not possibly interest & gain the affections of the natives. . . . They [the natives] did not love your sister. . . . That she felt a deep interest in the welfare of the natives, no one who was at all acquainted with her could doubt. But the affection was manifest under false views of Indian character. Her carriage toward them was considered haughty. It was the common remark among them that Mrs. Whitman was “very proud” (Perkins in Drury, II, 393).

Narcissa and the Whitman Myth: Some Lessons for Evangelists and Church Planters

The shaping force of the Whitman Myth in the story of Narcissa Prentiss Whitman gives rise to some lessons and reflections for Christians and their communities who are engaged in evangelism and church planting in the Pacific Northwest.

- Myths that surround the story of Christian leaders, including especially evangelists and church planters in the Pacific Northwest, can hide rather than reveal truth about their lives and ministry.

- Political and cultural forces can create powerful public personae—“masks” for religious leaders that commonly distort or destroy their God-given vocation and identity. Although this article refrains from identifying any recent evangelists and “successful” church planters, one could easily name, simply from reading the news, several highly visible and tragic examples of this situation in the Pacific Northwest in recent years.

- Understanding Christians from the past—as well as Christian celebrities of the present—involves disentangling the story of their lives from popular myths of heroic fame. Naively following in the footsteps of Christian celebrities of the past and present means that young evangelists and church planters will eventually discover the “clay feet” of their mentors.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cebula, Larry. Plateau Indians and the Quest for Spiritual Power, 1700-1850. Lincoln, NE: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2003. See especially the final chapter, “The Rejection of Christianity, 1836-1850.”

Cranston, Paul. To Heaven on Horseback: The Romantic Story of Narcissa Whitman. Fifth ed. New York: Julian Messner, 1952.

Daugherty, James. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman: Pioneers of Oregon. New York: The Viking Press, 1954.

Drury, Clifford M. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and the Opening of Old Oregon. 2 vols. Seattle, WA: Pacific Northwest National Parks and Forests Association, 1994, c. 1986. Drury offers the best published collection of primary sources for the Whitmans’ life and ministry.

Eaton, Jeanette. Narcissa Whitman: Pioneer of Oregon. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1941.

Hutchison, William R. Errand to the World: American Protestant Thought and Foreign Missions. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1987.

Jeffrey, Julie Roy. Converting the West: A Biography of Narcissa Whitman. The Oklahoma Western Biographies series. Norman, OK: Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 1991. This remains the best available critical biography of Narcissa Whitman.

Johansen, Dorothy. Empire of the Columbia: A History of the Pacific Northwest. Second ed. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

Perkins, Rev. Henry K.W. Letter to Jane Prentiss, October 15, 1849. Rpt. Clifford M. Drury, Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and the Opening of Old Oregon. 2 vols. Seattle, WA: Pacific Northwest National Parks and Forests Association, 1994, c. 1986. Vol. II, Appendix 6, 390-394.

Sabin, Louis. Narcissa Whitman: Brave Pioneer. Illustrated by Allan Eitzen. Mahwah, NJ: Troll Associates, 1982.

Scalise, Charles J. “Varieties of Victimhood in the Pacific Northwest: Conflicting Legacies of Narcissa Prentiss Whitman (1808-1847).” Presented at Christ and Cascadian Culture: An Interdisciplinary and Ecumenical Christian Conference. Seattle, WA, September 26, 2014.

Whitman, Narcissa. The Letters of Narcissa Whitman. Fairfield, WA: Ye Galleon Press, 2002.