The art of postmodern collage might seem disorienting, but it has something to teach the Church.

Last April, I took thirteen students from Columbia Bible College to the Vancouver Art Gallery to see a show called MashUp: The Birth of Modern Culture. The exhibit was focused on collage. We explored four floors crammed full of artwork created from other pieces of art/culture in every imaginable genre: Hannah Höch’s magazine collages challenging ideals of beauty and female roles; the first sampled dub beats of “King Tubby” and “Scratch;” Brian Jungen’s elaborate Aboriginal masks made out of Nike Air Jordans; Stanley Wong’s entire room (décor included) completely coated in red, white, and blue stripes. Later I asked my overwhelmed students what they thought. After a brief moment of weighted silence a single student answered. “I thought I was starting to understand what art was, but now I have no idea. I don’t even know where to start.”

Creative Theft

Borrowing from other works is a basic part of the creative process. We create not ex-nihilo, but ex materia—not out of nothing, but out of something. We create with wood, or paint, or clay, but also with the work of every artist that has gone before

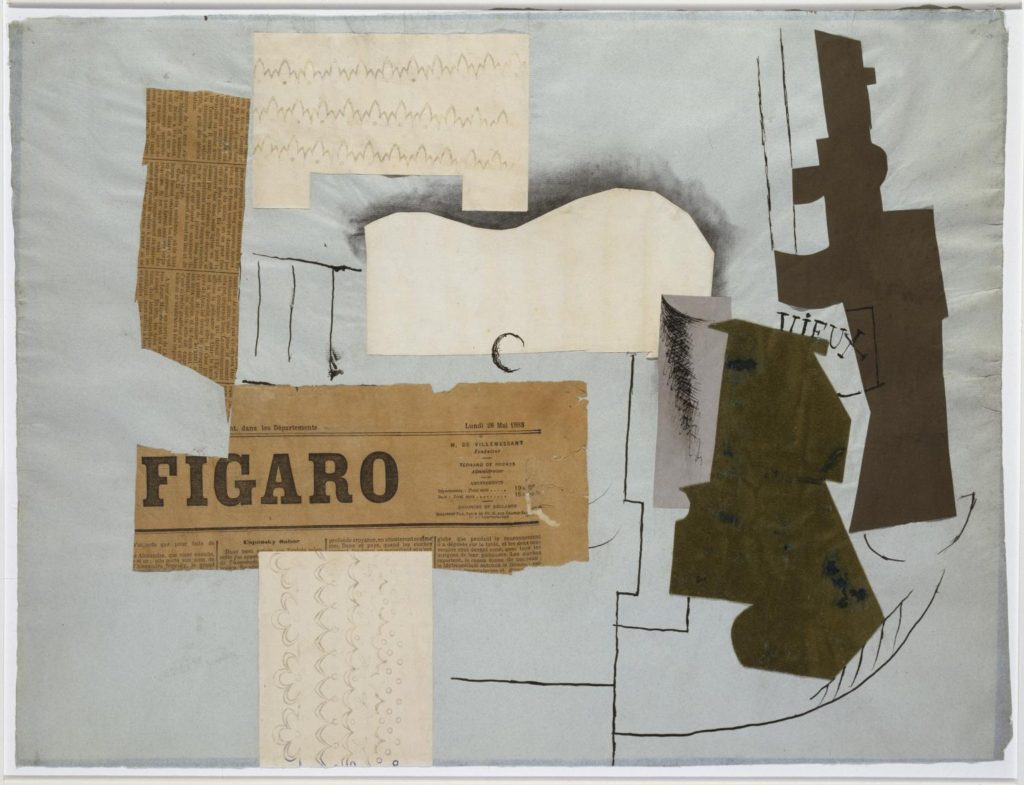

But one hundred years ago something new began in the art world that continues to this day.

The collage.

What Picasso and Braque started with paste and paint on canvas, we’ve pushed—through modern technology—into a world of artistic choice that is unprecedented. I can sample Bach, Aerosmith, and Beyoncé and layer it over “Funky Drummer” by James Brown. I can cut out the foreground figures of Grant Woods’ “American Gothic,” paste a modern city-scape photo behind them, add some flyer ad headlines, and loosely paint a segment of Van Gogh’s “Starry Night” over the entire thing. The choices available to the contemporary artist are nearly limitless.

Religious Decoupage

Postmodern culture is likewise enamoured with choice. We love a good collage, especially in Cascadia. The idea that we are a mosaic, not a melting pot—an idea taught by my elementary teachers as a way of defining Canadian culture against American culture—has been embraced in nearly every aspect of Cascadian society. It has certainly been embraced in the area of religion. Collage could almost be described as Cascadia’s defining moral code.

Spirituality is too often treated like a canvas: scissors and paste in hand, one piece is snipped out of this religion and one piece out of another. Even if I stay within the bounds of Christianity, I not only have the freedom but the imperative to pick and choose which hermeneutical trail I follow. This often depends on little else than what I want a certain passage to reveal about God, about the church, or about the world. And once I’ve gathered all my snippets together, I bring out my can of paste and create something new on my spiritual canvas. The gospel according to Stacey. My unique brand of spirituality.

It’s even more daunting for my undergraduate students. They’re just picking up scissors to cut and paste their own choices onto the family portrait they’ve been handed. Professors in Cascadia hear many variants of my student’s response to MashUp. “I thought I was starting to understand what Christianity was/the Bible says/what it means to follow Christ, but now I have no idea. I don’t even know where to start.”

A Third Way

It’s compelling that the Vancouver Art Gallery exhibit was subtitled “The Birth of Modern Culture.” Students are often responding to modern theological culture when they feel unstable in their faith—when learning that translation is synonymous with interpretation, or that new archaeological discoveries continue to shed light on Scripture, or that the canon of Scripture took hundreds of years to develop.

Many of our students come from Christian homes where they were given a narrow portrait of what Christianity should look like. At the same time, they’re also profoundly influenced by a culture that touts personal collage as the primary way of knowing and being in the world. Some shut down. They return to their family portraits wholesale. Others take out their scissors and paste fragments onto canvas with desperate abandon and little discrimination. But there is a third way.

I chose to explore MashUp from the fourth floor down. The top floor hosted older artwork, the first star-bursts of creativity inspired by Picasso, Braque, and their contemporaries. While some accomplished robust critiques of politics and societal norms, others seemed to glory in a new-found sense of disorganization. One piece in particular—a film by Joseph Cornell, the first to apply collage to film—overlaid clips with a soundtrack that directly opposed what the eye was seeing. The result? Extreme disorientation. Much like my students’ reactions to their religious portraits.

As I continued down through the floors of Mashup, that first bewildering burst of creativity was—not tamed exactly, but framed. The mash-up of various art forms carried deeper capacity for meaning as they re-tied themselves to structure.

A closer tie to structure didn’t rob pieces on the lower floors of creativity. Instead, artists used recognized rules to spark their creativity to new heights. These boundaries allowed the pieces to carry a huge weight of meaning that would otherwise have been impossible. Instead of being a collection of scattered fragments, the art of collage (or mash-up) became a series of intentional juxtapositions that contributed to meaning.

These artists show us the third way. We cannot separate students, or ourselves, completely from the influence of postmodern culture. If we were to attempt this, we would cut ourselves off from the ability to “seek the peace and prosperity of the city” in which we live in exile, as Jeremiah 29:7 puts it. But nor would I suggest that we give in with abandon to our culture’s disorienting collage of morality and faith.

In the end, our own personal portraits won’t be a mash-up of random things haphazardly thrown together. Rather, they will reflect the beauty of the kingdom of God on earth. Artists have an innate drive toward structure. This was evident even in a gallery exhibit intended to celebrate a creative break from the previous boundaries of art. And like them, we need to push towards Order, even as we create our own collage. The framework of the creeds needs to guide our cutting. The structure of our shared affirmations (the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, for example) needs to direct how we arrange the pieces. Only a full recognition of what does not move (the spiritual rules of composition and colour, if you will) allows us to make decisions about what does.

It is this structured yet wild creativity that should typify the church in Cascadia. The diverse expressions of faith that I see around me encourage me. They speak to me of the body of Christ enfleshed in this time and in this place—faithful to what has always been true, willing to grapple with the realities of a shifting and changing world.