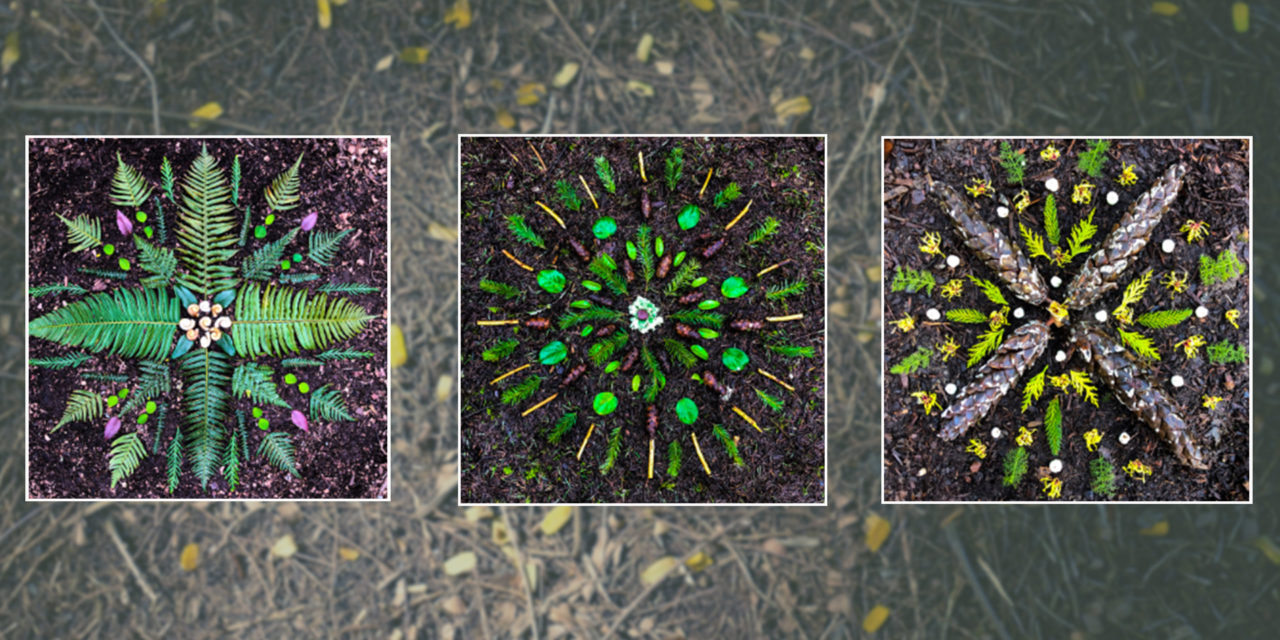

Photos and art by Mary DeJong

Fire of the Holy Spirit,

life of the life of every creature,

holy are you in giving life to forms.

Rivers spring forth from the waters

earth wears her green vigor.

–Hildegard of Bingen

I walk serene through my neighborhood woodland, stepping softly through blankets of white powder, brushing against fine, drupe-filled branches of snowberry. If I squint my eyes just so, I can discern the faint traces of emerging green: Indian plum is already beginning to leaf out in this Seattle urban forest, a sure sign of hope-filled life in these wintry conditions. I am filled with gratitude for the quiet and calm—the stillness of this season, and my connection with this place.

This moment of mindful reverie stands in stark contrast to the suffering this season has brought in other places. This winter has brought storms that have devastated the Northeast with ice and below-freezing temperatures, and crippled Texas with uncommonly fatal cold snaps—raising death tolls and compounding the suffering of communities already quarantined in response to the novel coronavirus.

This bitter season of devastation follows in the wake of the West coast’s worst period of fatal forest fires that threatened the habitat and homes of hundreds of thousands of lives. Five of the top 20 largest California wildfires fires occurred in 2020. These fires, and their accompanying rolling electric blackouts, were indiscriminate in their impact. Yet they spoke a collective message to which we dare not close our ears: Our house is on fire.

The Greek word for house is oikos; it also means home and habitat, a place that holds life and constitutes conditions for that life to thrive. It is the root of our word ecology, which literally means the study of our house or habitat. Oikos means the “whole inhabited world” or “the inhabited globe.” Oikos is our Habitat Earth, our Habitat Home.

And our home is burning, literally and figuratively. The Amazon rainforest is being cleared and burned, and the Congo River Basin is being put to the torch. Oceans are warming, and storms are becoming more severe and frequent. Biodiversity is plummeting, and ecosystems are collapsing. This is the age of the Anthropocene—the age when human activity has become the dominant and devouring influence on climate and the environment. This is the age when, in many ways, humanity itself is a voracious fire, rapaciously consuming everything in its path.

How ought our faith respond to this crisis? How do our theologies—the religious stories we tell about the nature of God and subsequently ourselves—respond to this ‘ecocidal’ reality that our oikos is going up in flames? For far too long, Christ followers have perpetuated the earth-dishonoring narrative that our true home is ultimately in heaven. As the old hymns of faith would put it, “This world is not my home, I’m just passing through . . . and I can’t feel at home in this world anymore.” We have been singing self-fulfilling prophecies while we set flames to our home, creating the very inferno from which we long to flee.

If there is to be any hope to stop this legacy of earth destruction, we must change our defining narratives. We would do well to recall that Adam’s name derives from the Hebrew adamah, meaning “ground” or “earth”; in creation cosmology he is formed out of humus—natural organic compounds, found in the soil, formed from the decomposed remains of other life forms. In resistance to tired and corrosive theologies then we must recover and discover stories that remind us of the truth of our existence: that we are created from this sacred earth and have the soil’s elements in our very bones. Environmental ethicist Larry Rasmussen reminds us that we are not so much at home on earth as we are home as earth.[1] We desperately need to recover the stories then that help us to re-member ourselves to this wild and wonder-filled truth: that we carry the sacred signs of oikos within our very bodies.

My knees are damp from kneeling in the forest floor duff. Gingerly, I remove a Western red cedar sapling from its pot—lifting it like a prayer, to set it into a small hole I’ve hollowed. Known in the traditional Lushootseed language as x̌payʔac, western red cedar is a species that is native to this urban woodland habitat, and one that is considered sacred by the Coast Salish peoples. Since 2007, I have been involved in a community effort to restore this patch that was once a degraded urban site. It was logged in the late 1800’s, when much of the timber was used to rebuild the city after the Great Seattle Fire of 1889. The land was thereafter neglected, and what grew back had little semblance to the original habitat. For me and my community, our forest restoration work aims to recreate the conditions in which the western red cedar might flourish, and helps to rebuild a home for this traditional symbol of providence and generosity.

The Duwamish people called this woodland slope qWátSéécH, meaning “Greenish-Yellow Spine.” The ancient name of this place hints at what it must have once been like: a rich and diverse ecology oriented around towering dark green conifers, and massive bigleaf maples that shone bright yellow in autumn. These restoration efforts of which I have been a part have thus been essentially about restoring this place to its name. Our work has been a process of re-membering the land’s stories as a way to rewild it, and restoring the myriad elements of a healthy, interrelated ecology that is grounded in this place.

As a people of faith, what are the stories that tie us to this place, this earth, this oikos? Hebrew scripture tells us that we were created out of earth, the primary incarnation and wild word of God. This would mean that we are made of the self-same sacred earth upon which we live out our lives. Yet rather than live as part of the land, we tend to live apart from it. Yet by recovering the sacramentality of our name, and reclaiming our sense of planetary place, we have the ability to change our defining story and our lived-relationship to the world. We are thus given the chance to shift our mode of being from a consuming people into a communing people—a people whose identity is shaped by a profound sense of belonging to place and planet.

If we do not seek to embrace this sacralized world-view shift, and if we do not root ourselves in the primary revelation of our essential connectedness to our earthen home, we will continue to set our house on fire. And as we destroy it, we will degrade our sense of God dwelling with us. For to apprehend God in all things is to understand God as permanently present to us in and through creation. When we engage the forest or the seaside, a fox or a butterfly, the sunset or the stars, we can sense the divine presence. Yet as our world becomes less resplendent, so too does our sense of God. When our environment becomes dismal and barren, our very notion of the divine becomes dull, and it becomes more difficult to imagine how we as human elements of creation might aspire to reflect the God who created us.

For our own sakes, and for the sake of the whole world, we need alternative stories. We need a sound and rooted creation theology—an understanding that God dwells with us in our oikos—an incarnate presence that liberates and regenerates all of creation, both human and more-than-human. In the Book of Job, we find clues for how we are to be in relationship with our places and listen intently to the sacred guidance given by the more-than-human world:

“But ask the animals what they think—let them teach you;

let the birds tell you what’s going on.

Put your ear to the earth—learn the basics.

Listen—the fish in the ocean will tell you their stories.

Isn’t it clear that they all know and agree

that God is sovereign, that God holds all things in God’s hand—

Every living soul, yes,

every breathing creature?

Isn’t this all just common sense,

as common as the sense of taste?”[2]

We are thus exhorted to court the wisdom of the wild. Not to corner it, capture it, or reduce its value to a commodified, objectified thing—for to do that would be to crush the very presence of God. Created beings have a subjectivity and personhood that cannot be controlled, coerced, or conquered. These wild ones—the untamed animals, lands, waters—have been given the gift of speech to tell us the truths that might save us; creation serves as a sacred script that reveals an ecological way of living that is essentially interconnected and interrelational. Creation holds a mirror to God as well, reflecting to us how to live in flourishing ecological relationality within our bioregional locatedness. Nature offers back to us our true name and speaks to us of what it means to live integrally with our planet and our particular places.

We need God to inhabit our places, and a creation theology framework for interpretation leads us to a deep sense of the sacramentality of all things. We are being called to attend to the wild scriptures that speak with birdsong and whale tears; that speak with winds and fire; that speak with twining roots of cedar and maple—and they would have us remember our ancestral name Adamah, “of the earth.” And in response, we are asked to fall in love with this beautiful wide, wild earth—in whose being we are profoundly and beautifully entangled.

I step gingerly over a great white western trillium, a restored perennial flower that grows wild once again in our woods. Its three-petaled face emerges out of tightly fisted fronds when the snows are gone. In ecologically-balanced woodlands, the presence of both conifers and deciduous trees are needed for this harbinger of spring to thrive—so it is for me a message of hope. I whisper gratitude to the spirit of this place, who has guided us in the rebalancing of its ecology the restoration of its storied name of this land. I remember that the Holy lives here in this house of creation, and I am drawn to come home to a sense of my own integral belonging to the oikos of this wild world.

[1] Larry L. Rasmussen, Earth Community, Earth Ethics (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1998), 90.

[2] Job 12:7-12 The Message (MSG)