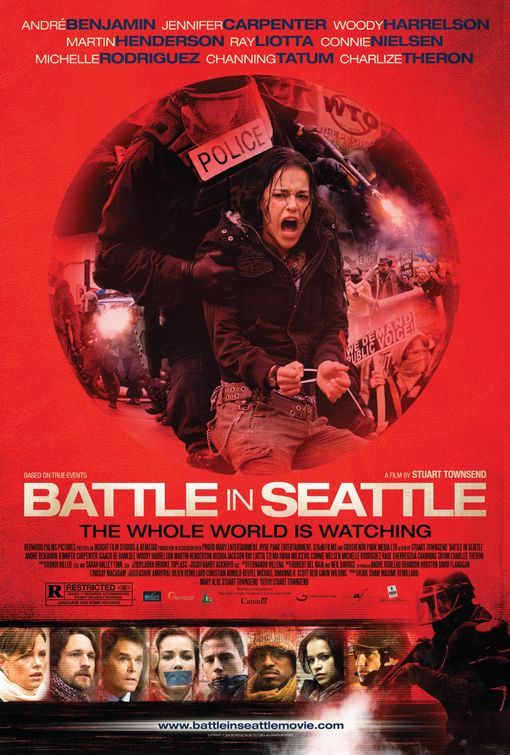

Do you remember Battle in Seattle?

Don’t worry. It made no lasting mark at the 2007 box office, and reviews were (deservedly) mixed.

I’ve finally seen it — seven years later, two months from the fifteenth anniversary of Seattle’s historic WTO protests. And (surprise!) it held my attention throughout.

It was a timely viewing choice, here in this season of protests.

While late-summer wildfires darkened my Eastern Washington horizon last month, another blaze scarred my social networks: “#Ferguson,” “#MikeBrown,” “#HandsUpDontShoot.” Links! Lectures! Laments! It seems everyone is upset about what happened when an unarmed black man in Missouri, hands reportedly raised, was repeatedly shot by a white cop before astonished witnesses. Scanning the outrage on Facebook was like listening to the shrill squeak of Sharpies on picket-sign cardboard.

And I had to ask myself: Why am I not tweeting my outrage? Have I been pummeled numb by scandal, injustice, and atrocity? Have I become hard-hearted?

I live in Seattle, after all: Home of “the 12th Man.” Seattleites cause earthquakes when they raise their voices against opposing football teams. And when corporate greed and abuses of power offend them, watch out — they’ll shake the world.

I fit a Seattle stereotype in so many other ways. I shop for organic produce. I mourn bookstore closures. I love the rain, the mountains, the melancholy.

But 15 years ago, as activists marched past my window at Seattle’s Department of Construction and Land Use, protesting the 1999 WTO Ministerial Conference, I kept working and went home to watch the news.

A paraphrase of those events, Battle in Seattle gives us characters who represent the conflict’s clashing factions: a mayor, a governor, a temperamental cop named Dale, Dale’s pregnant wife Ella, civilly disobedient objectors, and violent anarchists. But it’s the protestors whose motivations are compelling.

So I ask myself: Would I choose differently now? Would I brave the tear gas and violence to stand up against oppression?

Now on Home Video: Urban Chaos! Global Oppression!

Stuart Townsend became famous when he was replaced by Viggo Mortenson in the role of Aragorn after Peter Jackson’s cameras started rolling for The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring.

Battle in Seattle, his directorial debut, should help us forget that. It resurrects late-90s Seattle with remarkable detail. Politics, protests, and people come alive with uncanny eyewitness accuracy. Footage from the actual conflict gives Battle breaking-news credibility, and an all-star cast does admirably understated work.

Battle in Seattle, his directorial debut, should help us forget that. It resurrects late-90s Seattle with remarkable detail. Politics, protests, and people come alive with uncanny eyewitness accuracy. Footage from the actual conflict gives Battle breaking-news credibility, and an all-star cast does admirably understated work.

The film opens with documentary-style exposition about the GATT: the post-war agreement on trade and tariffs that was signed by 23 nations in 1947. The GATT, we’re told, was intended “to liberalize and expand world trade. Stability, a sense of global community — they were the key.” But as the GATT grew into the World Trade Organization, boasting 150 member nations, it also gained control of 90% of world trade, and began operating without oversight or governance.

Many distrust the WTO’s controllers and demand accountability from corporations who cross borders without oversight or transparency. Some argue that companies are getting away with murder, but who has the resources to push back? Thus, activists say, we must engage in civil disobedience to expose the injustice.

Moviegoers might expect Battle in Seattle to sum this up as the rebellion against the empire. But, for a 99-minute paraphrase, this movie is surprisingly nuanced.

First, the bad news: Battle in Seattle casts its narrative net far too wide for a 99-minute picture. It’s more successful at making points than developing characters. (It falls flat in depicting Seattle’s mayor and Washington’s governor — unconvincing approximations of Paul Schell and Gary Locke). This story needs a large canvas, a miniseries like The Wire.

Now the good news: It embraces complex moral ambiguities. Even as it favors the protestors — actor Martin Henderson looks a little too much like Jesus (or Aragorn?) — Battle in Seattle dares to show how even a well-organized nonviolent protest can (and probably will) attract irresponsible and dangerous players — namely, anarchists.

As media coverage turns into a feeding frenzy, two admirable figures (Rade Serbedzija and Isaach De Bankolé) intent on raising awareness about urgent global needs can only stand by helplessly, drowned out by hysteria.

The film’s most affecting storyline involves two characters: Officer Dale (Woody Harrelson), whose misgivings about the instructions given to riot police kindle his unstable temper; and his wife Ella (Charlize Theron) who, shopping for baby clothes in a department store without caring about sweatshop injustice, stumbles into the consequences of police misbehavior. It feels a little melodramatic, this “pregnant woman in peril” subplot. But I think Townsend wants to remind us that the next generation will pay the cost of ignorance and excesses.

“Protests get me excited and depressed at the same time,” says a feisty protester named Lou. That’s a pretty good summation of this film.

Seattle’s Complicated Passions

It’s easy to float theories about why Seattle became the world’s WTO battlefield.

The WTO increases in power without much resistance because most people don’t understand what’s at stake. But Seattle is a hotspot for readers, thinkers, and scholars — it’s #6 in Forbes’ “10 Most Educated Cities in America” and #5 in Amazon’s “Top 5 Most Well-Read Cities.” We Seattleites eat, sleep, and breathe news. Reading between the lines, we know our core values are threatened.

The WTO increases in power without much resistance because most people don’t understand what’s at stake. But Seattle is a hotspot for readers, thinkers, and scholars — it’s #6 in Forbes’ “10 Most Educated Cities in America” and #5 in Amazon’s “Top 5 Most Well-Read Cities.” We Seattleites eat, sleep, and breathe news. Reading between the lines, we know our core values are threatened.

What’s more, we’re literally “on edge” — the West Coast. We’re defined by the pioneering, progressive spirit that drove explorers westward. We love, and struggle to preserve, the Pacific Northwest’s wild beauty (or what’s left of it). “If you don’t stand up and fight,” promises a Battle in Seattle protestor, “everything that’s beautiful is gonna be taken away.”

Here’s a more cynical perspective. Perhaps Northwesterners find it easier, keeping our distance from the nation’s corridors of power, to rant like naïve and self-righteous adolescents, distrusting and resenting authority. Or perhaps we like our independence out here. We’ll do things our own way with as little supervision and interference as possible, and we’ll rail against change we cannot control.

I honestly don’t know.

I grew up as happy as a Douglas Fir between the Pacific and the Cascades, breathing coastal air. But I suspect that my convictions have more to do with my faith than my location. The psalms taught me to read nature as one of God’s most eloquent languages. I’m sickened when I see runaway commerce laying waste to resources God told us to “subdue and replenish.” I cannot reconcile Christ’s call to care for the poor with the rapidly expanding economic chasm between what some call “the 99% and the 1%.” We’re dishonoring our children, our grandchildren, and our Creator as we wait for others to change their ways without changing our own.

Thus, movies like Battle for Seattle make me want to lash out.

But then I remember.

Hard Lessons in Protest and Wisdom

I felt a similarly religious zeal when, as a much younger man, I joined some fellow students in assailing school administrators over the dismissal of a mentor. We assumed the school’s decision was the result of cutbacks. What was the real bottom line — education or money?

The door opened. An administrator — stone-faced, silent — listened as we pled our case. We departed in a rage, furious that our arguments were insufficient. We discussed how to take our quest for justice to another level.

God’s word tells us to “Seek justice.” Right?

But it scares me to think how much damage we might have done if we had acted on that impulse. Many months later, at a quiet corner table in a pub, a friend quietly divulged how our revered mentor — the one we’d labeled a victim — had violated her trust. I’d been missing the puzzle’s most important piece.

“Seek justice” sounds a little less Braveheart when you read the rest of the instruction: “…love mercy, and walk humbly with your God.” The school’s administration had administered justice, mercifully respected my friend’s request for privacy, and humbly refrained from smirking at our ignorance and scorning our self-righteous ruckus.

My naiveté exposed, I was humbled — no, I was humiliated. Perhaps that explains my reluctance to carry picket signs and join marches.

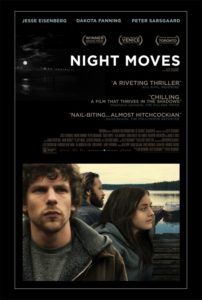

It happened decades ago, but those feelings returned as I watched Kelly Reichardt’s latest film.

Night Moves is a moody thriller about three Pacific Northwest environmentalists who carry their convictions — convictions I admire — to extremes. Their severe protest backfires in devastating fashion. And, unlike Battle in Seattle, Night Moves makes no effort to sanctify anyone. Rather, it echoes the Scriptures’ admonition that those who would pull up “weeds” may well uproot “the wheat” as well.

Night Moves is a moody thriller about three Pacific Northwest environmentalists who carry their convictions — convictions I admire — to extremes. Their severe protest backfires in devastating fashion. And, unlike Battle in Seattle, Night Moves makes no effort to sanctify anyone. Rather, it echoes the Scriptures’ admonition that those who would pull up “weeds” may well uproot “the wheat” as well.

Neither film will be remembered as essential cinema or visionary political engagement. But as a double-feature, Battle in Seattle and Night Moves might inspire enlightening conversations. That’s the advantage of art: direct confrontation provokes defensiveness, but art invites us into a state of openness and receptivity, that we might see things in a new light.

For me, these films reinforce the truth of my experience. Any champion’s quest for justice is likely to do more harm than good unless he’s inclined toward mercy and humility, serving as the hands and feet of Christ, keeping in view that in God’s grand scheme no one really “gets away with” anything.

Besides, Jesus led by example. He suffered the greatest injustice of all, and responded not with violence but with a shining and ultimately irresistible love.

Come to think of it, there’s a great deal of overlap between the Northwest’s zeal to educate the world about consumer responsibility and social justice and the zeal of evangelical Christians to proselytize and make converts of unbelievers. A word from Madeleine L’Engle might speak powerfully to evangelists and protestors of all stripes:

We do not draw people to Christ by loudly discrediting what they believe, by telling them how wrong they are and how right we are, but by showing them a light that is so lovely that they want with all their hearts to know the source of it.1

1 Madeleine L’Engle, Walking On Water: Reflections on Art and Faith (North Point Press; Reprint edition), 122.