As we prepare for our upcoming Christ & Cascadia Gathering and Reimagining Preaching Conference, we are beginning to explore this year’s theme of bringing the Word to life. How do we as Cascadians engage Scripture and communicate its eternal truths in this particular context?

The following article is a sermon given by Lauren St. Martin at First Covenant Church Seattle during their annual Julfest service (a Scandinavian Advent celebration honoring St. Lucia). In it, Lauren weaves Scripture together with denominational tradition, her family’s story of resilience and survival, and a call for empathy and justice. This sermon demonstrates how Scripture can help us develop empathy and place timeless truths in the context of today’s challenges.

Just a quick poll: how many here in the room are Swedish, at least in small part? Just raise your hands. Ah yes, we have the Andersons and Carlsons, Johnsons and Larsens, Blomgrens, Blomquists, Nelsons and Nilsons, and I’m sure many others. There’s a lot of Swedish heritage in the room tonight. That’s why we celebrate Julfest, right? Because the Covenant denomination of which this church is a part was founded by Swedish immigrants who came here generations ago seeking a better life.

Many of us, as we’ve seen, still have Swedish roots; but others of us are honorary Swedes tonight, like me. I am exactly zero percent Swedish, but I love this tradition. I love singing in Swedish (or trying to), eating spritz and Pepparkakor, watching the Lucia pageant. And I’m glad to be part of a denomination, a church, that was started by Swedes of deep faith and piety. They are some of my spiritual ancestors.

Some of my familial ancestors are Armenian, and over the years, it’s been important for me to learn about my Armenian heritage. And this isn’t just because it’s a beautiful, vibrant culture, but because it was almost entirely extinguished. Ethnic Armenians, who lived for generations throughout what was the Ottoman Empire, they were systematically removed from their homes and exterminated at the beginning of the 20th century.

Let me give a very brief history lesson here for context. Beginning in 1915, during the chaos of World War I, the Young Turks, who were a sort of transitional government between Ottoman rule and the establishment of the nation of Turkey, decided that Armenians were a threat to the developing national identity of the state. They used them as scapegoats—blamed them for their problems, accused them of being traitors and murderers. And then they did what governments do to those they deem traitors and murderers.

At the time, there was no word for what was happening to the Armenians. But it would come to be known as genocide—the first recorded genocide of the modern era (though some, including the Turkish government, deny it to this day). And not to kill the festive mood we have going here, but this genocide was the blueprint that Adolf Hitler used in his campaign against European Jews during World War II. Hitler famously said that the world wouldn’t care if he exterminated the Jews because, “After all, who remembers the Armenians?”

My great-grandparents’ family came from an Armenian village in Syria called Kessab. My great-grandfather owned a store, selling flour and olive oil made right there in Kessab and the neighboring villages. Around 1914, he left Kessab and journeyed to America. He planned to get settled and then bring my great-grandmother and their children across once he was established. But while he was gone, Kessab, like all other Armenian villages in that area, was emptied by the Turkish military. They came through Kessab and forcibly removed the Armenians from their homes.

My great-grandmother, Iskouhy Bohosian, had to evacuate with all six of her young children. And it wasn’t as if she could pack them all in the family minivan and hit the road. They traveled on mules through the desert, and when they no longer had the mules, they walked. Some of them did not survive the journey. Two of the young girls were taken away by Turkish soldiers, never to be seen by their family again. Others died of starvation.

Iskouhy and two of her six children survived and escaped to America with the help of some Christian missionaries. She was reunited with her husband, and it was there in their new home in Pennsylvania that my grandmother was born. Unlike many of her siblings, she would live a long, full life. She lived to be 102, in fact, and I had the joy of learning the stories of our family from her. We also have a cherished recording from Uncle Jack, one of the two surviving children. Before his death, he recorded his story: growing up in Kessab, being forced out, surviving in the desert, and coming to America.

My family recounts that story–the story of how we escaped and came to America–regularly. And remembering that story reminds us of a few fundamental truths that have shaped our family.

First of all, we remember that it is our faith in God that will sustain us, through whatever we must face. My great-grandmother, Iskouhy, was a woman of profound faith. And it was that faith that gave her the courage, the resilience, she needed to walk across the Syrian desert, to endure unspeakable loss and pain, and to still have hope for the future. Thanks to her unrelenting faith and the faith of those missionaries who made it possible for her to reach America, our family survived when many others did not.

Second, we remember that the safety and security we now enjoy are not guaranteed. We can’t take what we have for granted, and we can’t keep it to ourselves. What we do have is to be shared. My grandmother was one of the most hospitable people I’ve ever known, and I have no doubt that hospitality was a virtue instilled in her by people whose very survival depended on the kindness of strangers.

Throughout his testimony, Uncle Jack talks about the few Turks who refused to comply with their government’s desire to rid the world of Armenians. Those who took pity on them and helped them along the way, giving them food or protection.

I thank God for those Turks, and for the missionaries who helped my family get to America, those people of faith who recognized the evils of what was happening and took a stand to help my family survive. And I thank God that America was a welcoming place for these refugees and so many others at the time.

Perhaps you also have stories like this in your past. Perhaps you have Irish heritage, and your ancestors came to America during the Great Famine in search of a new beginning. Perhaps your ancestors were religious minorities who escaped from some country where religious freedom was not tolerated at the time. Perhaps you’re the descendant of Africans who were forced into slavery and have had to make a home in the land of their captors.

It’s important for us to remember those stories and the lessons they teach. We can draw strength from our immigrant heritage, and we can draw empathy from it, as well.

And even if you don’t know the stories of your family’s past, we can all remember that our Lord and Savior, himself, spent time as a refugee. We just read the story in the Gospel of Matthew that talks about how Jesus, too, was a refugee. Like my ancestors, perhaps like yours, Joseph and Mary were forced by the threat of violence to leave their home. They escaped to Egypt when King Herod threatened the life of their child, and they did not return until Herod was dead. (Matthew 2:13-15)

It’s such a short passage in the Bible, just a brief reference, but I think it’s becoming an increasingly important note for us. After all, we are living through the largest displacement crisis ever recorded.

There are more displaced people, more immigrants and refugees, now than ever before. Worldwide, one of every 100 people is now forcibly relocated; they’ve had no choice but to flee their homes. More than 100 million people, 100 million people, are currently displaced, and 41% of them are children. Children, like my Great-Uncle Jack, like Jesus, who have nothing to do with the geopolitical dynamics that are stripping them of their childhood. (Statistics from Covenant World Relief and Development)

More than likely, everyone in this room tonight is a descendant of immigrants and refugees, even if it goes back many generations. And we need to remember those stories so that we retain some empathy and compassion for what millions of people in our world are enduring today, so that we don’t prioritize our own comfort or convenience over the survival of others.

In the Old Testament, the second most common command, after the command to love God, was the command to welcome the foreigner, the immigrant. Throughout the books of Exodus and Leviticus, God encourages the Israelites to remember that they were foreigners in Egypt, that they themselves were oppressed, and so they should be empathetic to the foreigners among them; they should care for them. Exodus 23:9 says, “do not oppress a foreigner; you yourselves know how it feels to be foreigners, because you were foreigners in Egypt.”

The only meaningful difference between us and those people trapped in refugee camps around the world is where and when we happened to be born. That’s the only meaningful difference between us and all those people whom Aaron and his coworkers at the International Rescue Committee support. One hundred and ten years ago, that could have been me. I could have been waiting in a refugee camp for an entry visa, instead of here in this warm, comfortable church, getting ready to drink lingonberry punch and eat cardamom bread.

Julfest is a time when we think about the power of Christ to bring light to the darkness. We think about the generous actions of Saint Lucia who gave up everything to share Christ’s light in tangible ways with those in need. We think of the faith of our spiritual forebears and how they strove to be Christ’s light here in America.

My friends, we still live in a dark world. We still live in a world that does not recognize the image of God imprinted on each and every human being. In this Advent season, may we think of those dwelling in the darkness around us, those hoping beyond hope that countries like ours will make space for them, that people like us will welcome them. As those who have heard and received the good news of Christ’s love and care for all people, may we reach beyond our comfort zone, may we step into the darkness around us and share the light, the hope of Christ, with those who need it most this season. Amen.

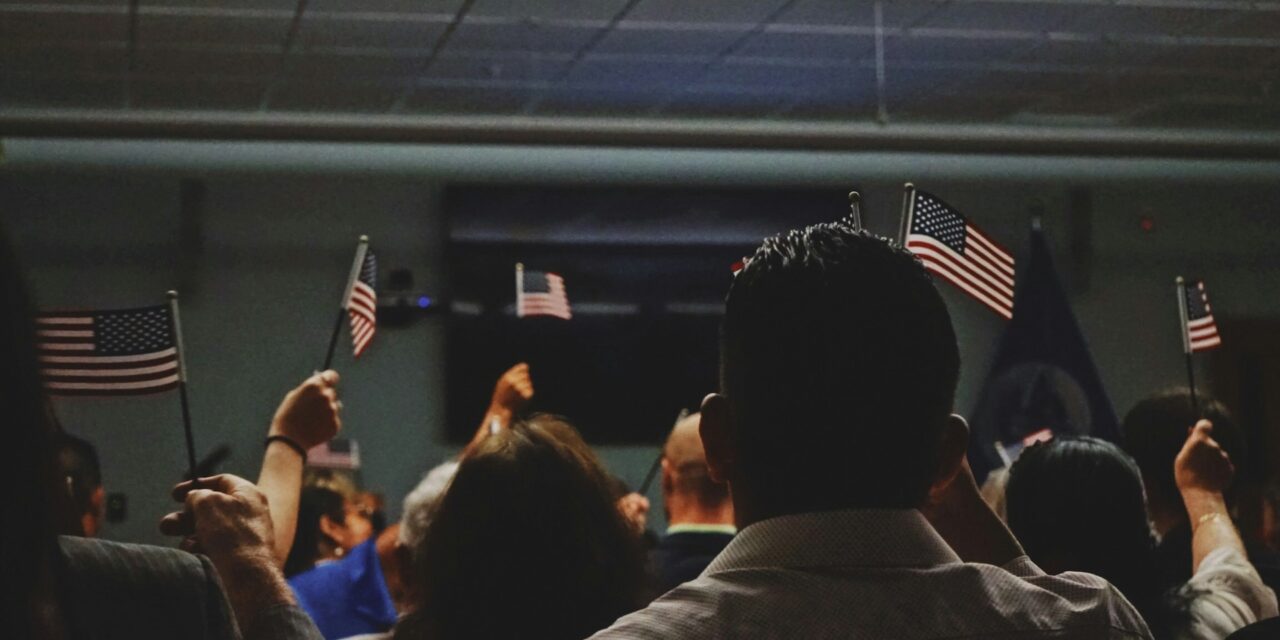

Cover photo credit: K E